Mike Somavilla Collection

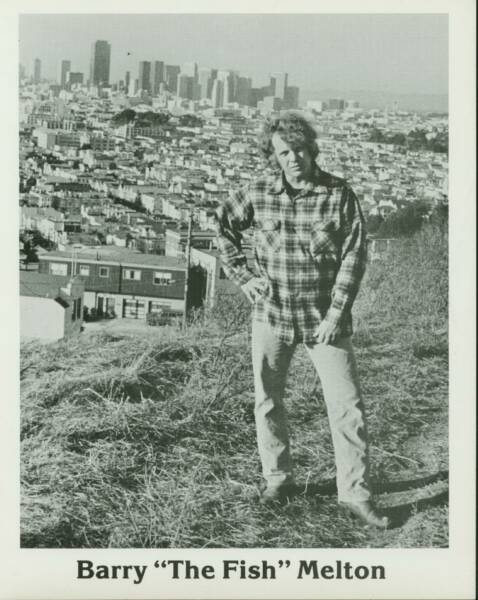

Barry "The Fish" Melton at Monterey Pop Festival, June 1967

Photo by Jim Marshall

Photo by Richie Unterberger

Click book cover to read more about Eight Miles High.

In 2003, Richie Unterberger's book Eight Miles High was released. Among many of the artists and bands that Richie profiled, there's an interview with Barry "The Fish" Melton, looking back on his work with Country Joe & The Fish, the life and times of the Sixties and other interesting recollections.

Richie has granted special permission to CJFishlegacy.com to reprint the interview from his book, uncut and in its entirety! My special thanks to Richie for his gracious contribution to this site!

Barry Melton Interview for Turn! Turn! Turn!/Eight Miles High

by Richie Unterberger

Q: Was it a conscious decision for so many young folk musicians of your generation to change to playing rock music in the mid-1960s?

BM: I think it was fairly conscious. I mean, we made a decision. As folk musicians. Folk musicians are sort of snobs, okay? And to a greater or lesser degree, we fashioned ourselves as purists, folk purists, that is. And I think in some senses, part of the folk music movement was from the purist point of view. When I was young and coming up in the folk music movement, I didn't want to learn music from records. I only was interested in learning through the oral tradition. Because that was what kept folk music pure. Right? You didn't learn it off records. You didn't learn it off the radio. You learned it from people. Which is the way it had been passed down for the entire history of humankind. I don't think it makes intellectual sense in retrospect (laughs), okay? I'm telling you, this is a mindset, okay?

And in some senses, we were victims of that mindset. Not entirely, because Joe [McDonald] grew up in El Monte, which had some great rock concerts in the early '60s and late '50s -- Fats Domino and the Penguins and all that stuff. And I grew up in the San Fernando Valley, and our big rock star was Ritchie Valens when I was growing up. I knew the music, and you couldn't go to junior high and high school, where I was going to school, and not be affected by rock and roll to some degree. Although I really wasn't interested in it, nor was I interested in playing amplified music. I was interested in being a folk musician. And I was very much into authentic folk music.

But I think what happened is, out there on the folk circuit and sort of infusing itself into the intellectual youth movement, for want of a better term, really well-executed electric music came along. And for Joe and I, our watershed for changing over is we both got extraordinarily stoned, and went and saw the Paul Butterfield Blues Band at Pauley Auditorium in Berkeley [in] late '65 or early '66. I think it was early '66.

Our first EP has a duet where Joe's playing acoustic and I'm playing an electric, and it's sort of transitional. But it's not really...it's not rock music. I mean, our first EP, it's folk style. It's a full jug band on one tune, and one of the guitars electrified on the other cut. Somewhere around that time we went to see them [the Butterfield Blues Band], and it was just...I mean, here were young white guys like us, making this really exciting music. We were kind of elitist, folk musicians. "Folk musicians were smart, rock musicians were dumb." In retrospect—I don't mean that. But it was part of our kid mindset. Part of mine, anyway. Rock music was something that was played on the edge of town by people who didn't have mufflers on their cars. Usually, in some place like the armory or something, at the edge of town. And folk music was played in coffee shops somewhere near the university campus. Folk music was legitimate, it was something you could discuss, it was the music of real working people (laughs). So were we [middle-class]. I wouldn't describe myself as upper-middle-class, probably lower-middle-class. But certainly not deprived by any means. But this was our mindset.

Q: Had you been playing anything like what you saw Butterfield doing?

BM: I was playing the blues by the time I was a teenager. And I was interested in playing the blues because it was wrapped in a whole series of political beliefs in which I was involved, which revolved around the civil rights movement. Here was the authentic music of the oppressed black rural south, okay? And that's what I wanted to play. I wasn't interested in playing bluegrass music, 'cause [it was] the music of the racists who were picking on people who were part of the black rural south. So it had a more political thing, although for various anomalous reasons I played Carter Family songs. But you don't have to be intellectually consistent.

One of the reasons why I chose to play blues rather than bluegrass is being sort of young and in the '60s and involved in the Civil Rights movement. Bluegrass music seemed like the music of the oppressor, and blues seemed like the music of the oppressed. I realized how silly and sophomoric that is in light of today's history, because in fact much of what we consider American pop music, is traceable to the rural South, and people in impoverished circumstances, white or black. The backbone of American pop music is poor Southerners who are white and black.

Q: What was the specific effect the Butterfield band had on you?

BM: They were phenomenal. It was blues. It was Chicago blues. And in fact, digging deeper after I heard that, I dug deeper and I got myself some B.B. King records and some Albert King records and some Freddie King records and so forth. And then started to go through the various stuff on the Chess label. But I guess hearing them, I realized that this was electric music, but it was incredibly authentic, so you could play authentic electric music. It had all the excitement of electric music, and it had all the intellectual cachet of folk music.

Q: The Butterfield band were playing folk coffeehouses at the time, which exposed a lot of folkies to this music.

BM: Absolutely. And that's what I'm saying. Here's this band that broke across the line, and became acceptable in the polite company of the folk community. They really broke the barrier. They were playing an acceptable idiom, because it was an authentic electric music. You can listen to the early Country Joe & the Fish, I mean the first Country Joe & the Fish record, it's by no means a blues record, not even close. It's just not a blues record. It's just that for, particularly our first EP, it's this weirdo wacko kind of middle eastern Japanese— it was much more San Francisco raga middle eastern-influenced stuff.

But in any event, the Butterfield Band was part of that decision. Some of the bridge people were the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and its neighbors. 'Cause I remember when [Butterfield guitarist Mike] Bloomfield was an acoustic blues player. And then somehow Chicago blues had a sort of folk legitimacy, even though it was electric. The other person I can think of who was like a real transitional figure for me in the legitimization of electric music was Lightning Hopkins, who did both. He was really big on the folk circuit, he was like a star on the folk circuit. He always put the people in the club. But Lightning, kind of like half the time, would play electric. I remember when he used to come Berkeley and play the Jabberwock. Sometimes he'd play acoustic, and sometimes he'd play electric. One of the people who used to play drums for Lightning when he came through was Rolf Cahn's son, and Barbara Dane was his mom.

Lightning was one of those bridges because he made...I don't know if you'd call 'em like pop records. I guess [he] made rhythm and blues records, like amplified. They weren't sort of like the full repartee of what we now consider to be a blues band. It was basically just his guitar part into an amplifier with maybe bass and drums. Maybe just drums. Lightning had a real authenticity on the folk circuit, and no one said boo when he would come amplified. And he pretty much did whatever he wanted to do (laughs). On a personal level, he was kind of caustic. He freely switched between 'em. You didn't know when he came into town to play your club whether he was going electric that night or acoustic, and it didn't seem to have any rhyme or reason or pattern. I consider him one of the genuine legimitizers of the electric form. So he's part of the equation.

There were some people who were allowed to sort of cross over. Lightning was one of them, and the Chicago blues guys. Lightning Hopkins was definitely thought of as an authentic blues singer, whether he decided to play electric that night or acoustic. So I think in a way, and I don't want to sound like a racist when I end up quoted, it's as if African-American musicians had permission to do electric music, but white guys didn't (laugh). Is that a weird thing to say? But I think somehow on the folk circuit, African-American musicians were given sort of permission to amplify if they wanted to. It wasn't necessarily extended to white musicians, and particularly young white musicians. When young white musicians did it, they were crossing the line of legitimacy to that illegitimate music which was known as rock and roll. Whereas when African-American people did it, it was like, that was a permissible extension of where the blues could go.

[Before seeing the Butterfield Blues Band], I never really considered playing rock and roll. I grew up in L.A., okay, so I was an Ash Grove [L.A. folk club] kid. David Lindley is from that group of folks, [as well as] Sol Feldthouse [who played with Lindley in Kaleidoscope]. So was Leo Kottke, sort of as an early L.A. guy who was sort of a follower of John Fahey's. And Al Wilson, I remember him as an L.A. folkie. And I remember David Crosby, and Steve Mann, who was an underground folk guitar player, was Sonny & Cher's first guitar player (laughs), had a lot of influence on early players. Dick Rosmini. A lot of instrumental L.A. musicians and guitarists. And Taj Mahal played in an electric band. He played with David Cohen, L.A. David Cohen, in King David and the Parables, which was the sort of Ash Grove mime troupe band. But I really was not interested in playing electric much.

Another L.A. folkie I knew at the time was Mike Wilhelm. I knew Mike from L.A., before there was a San Francisco scene. And had met David Crosby and Jim McGuinn through my friend Steve Mann, who was a studio guitarist, folk guitarist, and one of the early white guys who could play the country blues. It was early '60s, like '63. And I was sixteen. By that time, I'd been playing guitar eleven years already, and I was sort of part of the L.A. nightlife, Ash Grove, McCabe's scene.

There weren't that many people. In retrospect it was fairly small. The Ash Grove was postage-stamp sized, in truth. The Ash Grove had like 50 seats in it, man. But it was home for all of us. It loomed like a gigantic thing in my past -- all these incredible performers, Mother Maybelle Carter, Doc Watson, Elizabeth Cotten, phenomenal icons of American music. That kind of music, which today, the equivalent would draw 1500 people in a theater, in those days, drew forty, fifty people. The music really didn't have an audience yet. It's folk-rock that made the audience for that music.

And then the guys from the East Coast would come through, like the Kweskin Jugband and Fritz Richmond, Doc Watson, and we'd all play together in the area between McCabe's and the Grove. So the folk scene was twenty people playing in at the same time kind of scene (laughs), and a real nursery for musical ideas and young musicians. That cross-blending ended up in rock with a little Doc Watson, B.B. King, Lightnin' Hopkins all mixed together, which you hear so much of in the folk-rock idiom.

Q: What kind of music were you and Joe playing before you went electric?

BM: Joe and I played as a duo. Our first record came out in October of 1965. And the first thing we did was we went on a tour as a duo for the SDS to northwest colleges playing folk songs. We had a lot of folk tunes in our repertoire, other than the originals that Joe was singing. And we were playing in this Instant Action Jug Band, which was kind of adjunct to the Jabberwock folk club in Berkeley. We did a lot of sort of, fifteen different folk musicians sort of standing on the stage together. Some of whom are still marginally around, like Alice Stuart and Phil Marsh, who later on formed the Masked Marauders. It was sort of this Berkeley folk group, and we sang things like "Sowing on the Mountain, Reaping in the Valley." You know, the sort of gospel tunes, and kind of Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly, and kind of folk standards that any group of fifteen folk musicians would know (laughs).

Then Joe and I went up. We toured as a duo, and were working fairly regularly. And we were doing this play in San Francisco called "Superbird," which was written by Nina Landau, who was then married to Saul Landau, who later become sort of a left-wing filmmaker and Fidel Castro's biographer. We were playing various gigs, hired by various political groups, campus groups and stuff. And then I got in a rock band with this guy David Cohen, and we started sort of rehearsing that while I had a job—Joe and I were actually making money working as a duo. And slowly, Joe was getting divorced from his first wife, moved into our house, and I was living there with my friend Bruce Barthol and this guy Paul Armstrong, who became the nucleus of the band. These were guys that I had been playing with anyway, sort of. We had been playing folk music together for a long period of time. Then we sort of rehearsed and put together this electric sound.

Q: There were a lot of personnel shuffles before the Fish had the lineup that recorded their first LP. Could you go through how such a diverse group of people coalesced? A lot of major folk-rock groups had a very unlikely combination of musicians.

BM: In the late spring of 1965 Paul Armstrong, who had sung on the streets of Paris with Phil Marsh (i.e., they were "buskers" together) was sharing an apartment right next door to the Jabberwock with my old high school singing partner, Bruce Barthol. They needed at least a third roommate and possibly a fourth, preferably musical...I was the third roommate and a neo-psychedelic classical guitarist named Robbie Basho became the fourth roommate several weeks later. Paul, Bruce, I lived mostly on white bread, peanut butter and powdered skim milk...and whatever food we could forage from the Jabberwock: After the customers ate, we came down and scoured the leftovers. The exchange was relatively fair, at least from the starving musicians' point of view: We were the core of the "hoots," the opening act for whoever wandered by on the folk circuit (for example, Lightnin' Hopkins, Sol Feldthouse, David Lindley (Sol and David were separate acts in those days, and later formed the group "Kaleidoscope"), Sandy Rothman (who was a real Berkeley "star," having toured with Bill Monroe), Ale Eckstrom from Sausalito (and Peninsula guys like David Nelson), Steve Mann, Barry Olivier and many others. All this, of course, was before the transition to rock music.

Sometime during the summer, I got a phone call out of the blue from some guy named Joe McDonald asking me if I wanted to make a record with him. He said I was recommended by Dan Paik, and Dan (who was exceedingly kind) said words to the effect of, "Barry Melton's really a better guitar player than I am—you should call him up." Dan was entirely too self-effacing: We'd been playing in some of the various jug band aggregations discussed above and he was every bit as talented as me. But Joe and I met, we had a kind of instant communication. Both of us were "red diaper babies" and had astoundingly similar backgrounds...his dad was from Oklahoma, mine was from Texas, and both of our mothers were East Coast Jews...we shared a mutual fondness for Woody Guthrie (Woody and his family had actually been neighbors of mine in early childhood and my dad was a friend of Woody's) and all things left in folk music.

So it turned out to be a great connection. We played, we rehearsed, we even rented an electric guitar from our mutual friend Campbell Coe who owned a small music store in downtown Berkeley that we eventually used on our duo song for the record, "Superbird." I, in turn, told Joe that I was NOT the best ragtime picker around and that we should bring in my friend Carvel Bass to pick on "Fixin' to Die," and that he did.

And, I should note, Joe was, in a word, kind of "straight" when I first met him and I elected not to pull any of my carefully rolled joints out of my guitar case when we met for our first rehearsal. After all, he was still in the Navy reserves, married and while he seemed to be a very political guy, I could tell he wasn't a "head." But I brought Joe over to our house, and introduced him to the Jabberwock group of folks, and eventually he began to become a regular in our scene and a regular in the ("Instant Action") jug band. This is the band that gets its own chapter title ("The Frozen Jug Band") in the Tom Wolf book Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

By mid-summer, Joe was coming over to our house regularly and began hanging with the Jabberwock crowd. At the time, Joe was living with his first wife, Kathy (not to be confused with the Kathy he lives with now, who is his fourth wife) on Grove Street (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Way) in Berkeley. Anyway, during October 1965 at or about the time of the Teach-In, there was a peace march that proceeded at points down Grove Street in front of Joe's house and the Instant Action Jug Band, which by that time included Joe, played for the march. But during the Teach-Ins themselves, Joe and I had a table in Sproul Hall Plaza and played as a duo to promote the record (none of the other Instant Action folks were involved in the recording) and we ultimately got booked on our first tour as Country Joe and the Fish as a duo, touring colleges in the Pacific Northwest on an SDS-sponsored tour (Lewis & Clark & Reed College in Oregon, University of Washington in Seattle). When we came back, we played a couple of dates at the Jabberwock as "Country Joe and the Fish" as a duo, but as Joe got to know my roommates they'd join in too.

Ultimately, we moved Basho out of the house (he was kind of a pain in the neck and difficult to room with), Joe split up with his wife and moved into Basho's room and David Cohen, who I was trying to form a rock band with, began to come over to the house and play with us a bit. We turned Joe on to acid (he needed it, or so we thought). I don't really know where John Francis came from, but that was the beginning of the band. Bill Ehlert let us use the Jabberwock, of course, as our rehearsal hall. Ultimately, when John Francis got "fired" during the rehearsals for the first Vanguard record, I found my friend Gary Hirsh drinking coffee at the Forum Cafe in downtown Berkeley and invited him to play drums with the band. Of one thing I'm certain is that when it comes to the band that played on the first Vanguard record, I was the "glue" that put the band together, since the one factor everyone had in common was a friendship with me.

One thing I can assure you of is that neither Joe, nor ED [Denson, Fish manager], nor I "decided to form a jug band" to politicize our audience. In fact, Joe joined an existing jug band aggregation made up of my roommates and the folks who hung out at the Jabberwock. But that aggregation is NOT the same lineup that appeared on the first EP record...which was a mixture of Joe's friends (Carl Schrager and Mike Beardslee), me and my friend, Carvel Bass on "Fixin to Die" and the Joe-Barry duo on "Superbird." That lineup for "Fixin to Die" on the record only performed once–in Chris Strachwitz's living room for the record. We never performed as Country Joe and the Fish before or after the record was made. The first EP record was, absolutely and without doubt, put together to sell at the Teach-In and we even had a table for the express purpose of selling our first batch of records right in Sproul Plaza during the Teach-In. We alternated between playing the record over a speaker system and playing the song live to whoever came by (and there were many tables there, but I think ours was the only one selling records).

Q: A lot of early Fish material has a pronounced raga-rock influence, like "Section 43," which was on both your second EP and then your first LP. How did that come into play?

BM: I think that was me more than anyone else. At least, that part of it. Because I was a big Hamza El Din fan, and sort of Sandy Bull fan. It's interesting that that happened, and I've come to know Hamza really well in years past. I sort of put Hamza together with Micky Hart, and set him on the road with the Grateful Dead in later years. And they all ended up in Egypt together, but that's another story.

Also, when I was in L.A., interestingly enough, among the other things that were going on in L.A., the World Pacific Studios were in L.A., which is where Ali Akhbar Khan first recorded when he came to the United States. And also there was a koto player in L.A. named Kimio Eto, who is this sort of westernized Japanese-American koto player, but sort of mixed the traditional Japanese koto with a sort of American influence. I learned from both of them, 'cause I heard both of them play a lot in Southern California when I was growing up. So I sort of brought that with me, that sort of Japanese and middle eastern influence, and Indian, the ragaesque thing.

Q: I think a bunch of folk-rock and psychedelic bands were influenced by Bull. His effect on the rock scene is underrated.

BM: And, in fact, [that influence was] incorporated into the Byrds. If you listen to "Eight Miles High," [the] solo in there, that stuff is close to that idiom. But he was also big in the drug subculture. Apart from everything else, he was legendary. 'Cause he was the guy who went to Tangier and lived in an opium den. Sandy was legendary in those days. Tangier was part of the folk circuit, because it was a place that somebody could legally go and smoke hashish, the verboten substance that was felonious everywhere in the United States.

Q: "Section 43" is a very interesting song in its blend of rock and so many other influences, and how it shows the Fish advancing so quickly to psychedelia. Also, you recorded it twice, first for your second EP and then for your first LP.

BM: We first recorded "Section 43" in approximately April 1966 for our second seven-inch, extended-play (EP), release on Joe McDonald and ED Denson's "Rag Baby" record label. It was the first recording of Country Joe and the Fish as an electric band and contained three songs: "Bass Strings," a song in praise of marijuana (opening with the lines, "Hey, partner, won't you pass that reefer 'round...), "Thing Called Love," a blues-based, over-abundance-of-testosterone, song about immediate sexual encounter (and there sure was a lot of that in those days) and, of course, "Section 43," an instrumental that occupied the entire second side of the EP. The lineup on that record was that of the original electric band: Paul Armstrong and Bruce Barthol alternating between bass and various percussion instruments (maracas, tambourine, etc.), John Francis Gunning on drums, David Cohen on guitar ("Thing Called Love") and keyboards ("Bass Strings" and "Section 43), Joe (guitar and vocals on "Bass Strings") and me (guitar and vocals on "Thing Called Love").

Joe and I had previously recorded our first EP with a wholly different lineup of musicians just before summer of 1965, in preparation for the first "Teach-In" against the Vietnam War held at the UC Berkeley campus. But the Country Joe and the Fish side of the first EP was half jug band ("I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die Rag," with Carl Schrager on washtub bass and kazoo, Joe singing lead, and also playing guitar along with me and Carvel Bass, and a guy named Mike Beardslee singing backup vocals) and the other half was the song "Superbird," done in semi-electric blues-rock format featuring Joe and me as a duo. The other side was a long version of a song called "Fire in the City" written and sung by Berkeley songwriter Peter Krug. As a matter of purely historical interest, "Fire in the City" was later recorded by the Grateful Dead with Jon Hendricks (yes, that Jon Hendricks, the jazz singer of Lambert, Hendricks and Ross)!

Anyway, back to Section 43...

Joe was a great admirer of John Fahey, as was I. And our Country Joe and the Fish manager, ED Denson (the first two letters of his name are capitalized--a nickname comprised of his initials [his real name is Eugene]) was from Takoma Park, Maryland, grew up with John Fahey and later co-founded the Takoma label with John. ED, I think more than Joe, had the idea that we could use Fahey-like compositional structures, which had discrete sections and/or movements, and incorporate them into electric music. Hence the four or five discrete movements of Section 43. But I think it's important to stress that both the first recording of Section 43 on EP, and the version later re-recorded for Vanguard and made a part of our first LP, are only recordings of '60s music—they're not the real thing. And I guess that's where the drugs come in.

Sadly, what survives of Country Joe and the Fish in recordings is only marginally representative of what we really did on stage. Fortunately, the Grateful Dead were able to survive long enough as a viable entity to give modern listeners a real taste of what '60s improvisational rock music was about. But in the early days, I think it fair to say that the Dead, Fish, Airplane, Quicksilver and Big Brother had one thing in common: Any of those bands might get up on stage and do 10 songs for an hour, or they might do one song for 10 hours!!! (Well, one song for 10 hours is no doubt an exaggeration, but it was not uncommon for us to get up on the stage so loaded that we did one song for an hour and a half, or two hours, after which a bunch of really anxious management types began drawing lines with their fingers across their throats [the old "cut" sign] and we somehow ended in some manner.)

In fact, in the early days before Janis joined the band, the highlight of Big Brother's set was an endless version of "Hall of the Mountain King" from Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt Suite #1 that inevitably ended up with James Gurley playing space guitar for enormous gobs of time. Why would anyone do one song for two hours, you ask? Simple: We were all so loaded we had no sense of time whatsoever. Recording, of course, "cured" us all of our ramble-on tendencies: But I am truly grateful that the Dead survived long enough (no puns intended), and to a point of maturity, where they weren't at all embarrassed about getting on stage loaded and going on for hours and hours.

I'm going tread dangerously into the shark-infested waters of sociological commentary. We were all "stoners" back then, and one of the first realizations borne of psychedelic insight is the inadequacy of language. In fact, I think every member of my band and any of the other bands called upon to play at political events was a bit angered at the fact that the politicos would use our music as a shill to lure crowds and then talk to them endlessly. And there is nothing more grating to a stoned audience than a bunch of people talking. Somehow, I believe what we all sensed was that whatever it was that was "high" about our music wasn't to be found in the words.

Rather, it was in the improvisational interplay between the musicians and those magic moments when we really got into the "zone," that magical place of near-enlightenment, approaching pure experience, when we truly escaped the smallness of who we were into a place far more expansive and reflective of an altered state or other reality. And I truly believe that's why the audiences came to hear our music—for the same reasons they later flocked to see the Grateful Dead—to see if we'd "get there" that night.

When we recorded "Section 43" on the first EP, we knew something was missing. Somehow, limiting the length of the song—squeezing it into the confining space of a single side of a small EP record—had drained much of the life from the music. Played live, the solos went on until the soloist was satisfied that the statement was made in full. But the recording process abbreviated the process into an attempt to incorporate the "best" parts of whatever we were doing without regard to the resolution that comes when soloing to completion. So, in full recognition of this problem (and perhaps because I articulated the problem so well), I was the member of the band nominated to do the "mix" of "Section 43" for the EP (actually, the other part of the rationale for choosing me to do the mix was that the engineer–Bob DeSouza–insisted he would NOT have the whole band there during the mixdown process for fear that the group as a whole would drive him completely crazy).

Anyway, I can assure you that I went to that first mixdown of "Section 43" in an appropriately altered state calculated to re-inject some magic back into the recording. More to the point, I believe took about as much acid as one can take without having the inanimate world turn completely into sponge rubber (my friends who are legal scholars should note that LSD was still legal in California in April 1966). And I did the best job I could possibly do under the circumstances. I think I got about 2% of what was missing back, just enough—I guess—to help build something of a legend for our band, land us a real recording contract and sell thousands of those EPs across the globe. Of course, the song was re-recorded somewhat differently for our first Vanguard LP; but aside from a few fade-ins, the essential "flavor" of the first recording was duplicated on the Vanguard cut.

I still believe that much of what was truly psychedelic about psychedelic music had everything had everything to do with the improvisational instrumental sound of the music and little to do with the lyrics and singing. Particularly, in San Francisco (and Grace and Janis aside), good singers did NOT abound. If "Section 43" is indeed one of the "100 Greatest Drug Records Ever," it would certainly be a great honor put the song in such an elite group considering the enormous body of great "drug records" that I know of. But I should guess that it will be one of the relatively few instrumental pieces included, and that's a shame. Because folks familiar with drugs, particularly psychedelic drugs, know that much of the "gris-gris" that comes from listening to music on drugs comes from the instrumental spaces, not the lyrics (in other words, please consider such greats as "A Love Supreme" by John Coltrane and other such instrumentals for the drug hit parade).

Q: It seemed like the Fish and a bunch of notable folk-rock bands made a quick transition from folk to folk-rock to psychedelic rock.

BM: You call psychedelic music a category, as if it is something that exists as a category. I don't think of it as a category. I mean, musicologically speaking, I don't think there's such a thing as psychedelic music. For purposes of convenience and lifestyle groupings, maybe you can call it that. But do you consider the Byrds psychedelic music?

If you were a professional musician in the '60s, and you got to a certain point, you were going to sound like that, 'cause everything that was selling was sounding that way (laughs). I don't mean that in a derogatory sense. What I mean is, those guys always had a profoundly good sense of the commercial anyway. The idiom was easy to understand, because it was a folk-rock idiom borrowing from jazz's ability to incorporate improvisation. But folk musicians improvised anyway; they just didn't let go of the anchor. And the only thing "psychedelic music" did was it jazz-ized folk music. Musicologically speaking, it was logical at a time when Miles Davis and Doc Watson existed on the same plane (laughs).

So I don't really think there's a form of music called psychedelic music. I think there's a sort of jazz-ized folk music, and that's what psychedelic music is. It's a blending of those two idioms. What you really have musicologically speaking is, you have a time when there's all these elements coming together, because of the power of the media, and the mobile society, and the intermixing of people from different backgrounds. We didn't discriminate between...I mean, I heard a lot of jazz during that period too. And jazz was authentic, and it was okay. It wasn't amplified, and more particularly, here we are in the middle of the civil rights movement, it's made by African-Americans. So jazz was okay. I mean, it passed the intellectual litmus test.

You must understand, when I say that, in retrospect, those ideas are silly. But we had 'em when we were kids. I mean, I was a teenager, and this was my view of the world. So what you call psychedelic music, to me, it's a combination of the jam sessions that I would have at the Ash Grove, playing some folk song interminably for fifteen or twenty minutes with everybody getting a chance to take a solo, right? And jazz, which allows you to let go of the chordal structure itself, and just sort of slip out there into space a bit, and suspend it for a while. Then you throw those two elements together, and you have what you call psychedelic music. Which is really a jazz-ized folk music, where you're allowed to suspend the chord structure for a period of time, and go out there and improvise in a really free space. But jazz did that way before San Francisco music got there. Lots of folks. Ornette Coleman was doing it, John Coltrane was doing it, so we could do it. With our folk idiom, it was okay to do it. We were listening to that music.

You know, rock music is the garbage can of music, or the melting pot, depending on what your attitude is (laughs). You can throw anything in the soup, and it just becomes like a big stew. You can keep throwing things in all day, and it will absorb it, and still be edible. It's like this giant soup that's cooking on the stove, where you throw in an onion, and an hour later you throw in a potato, and it all gets dissolved in there. So in a band like Country Joe & the Fish, we could absorb jazz and Japanese music and middle eastern music and Indian music and blues music, country music, it all fit in there somewhere. It was okay to do that. For a lot of folk musicians, particularly guys like me from fairly urban areas, here was a chance to throw in all the stuff that we knew—everything from Pete Seeger and the Weavers to John Coltrane—in one place. And have it all happen in the same place, and have it all integrate. Through that melting of all the influences that we have—and every person who ever played the Ash Grove, all the blues musicians, the Carter Family, Maybelle Carter used to play the Ash Grove, and the Stanley Brothers, and Lightning Hopkins— you take it all in a big stew and throw it in together and viola, you've got folk-rock.

With the jazz thing, when you get out there, it's really taking chances. Because it works sometimes and it doesn't work sometimes, so it's really based on whether you're on or off that day. That's the most dominant element in the success of the music. Some days it flows, and some days it sounds deader than a doornail. The Grateful Dead managed to stay together, managed to make that a very salable commodity, into the '90s. And it was, at its roots, that jazz-ized folk music.

Q: What was the reaction like when you starting playing electric rock?

BM: Once we hit into the electric medium and into the rock medium, we were pandering to the public taste. We became extraordinarily popular, and then the little folk club where we used to play once every two weeks, we played every single night for a month, or something like that, and filled it. After a while we filled two shows a night every single night [at the] Jabberwocky. As folk musicians, what really happened is there was a split in the music community, where some people did not want to, and refused to, go into the electric medium, and some people did. And there was a break within the musical community. Forget the audience. The men and women who played acoustic music suffered for years. They were like punished by having to labor in obscurity for a considerable period of time as a result of not making the transition. Some people tried the transition, and it wasn't a successful transition, and had to go back. Particularly I think of, like, Taj [Mahal] tried his experiments with electric, and went back. David Lindley tried his experiment with electric, and went back, for example.

So in the musical community there was a split. What's most interesting to me, I'd say, in last fifteen years or so, the folks who stuck with acoustic have been on the ascension, at least in my perception. Somewhere around the time that Unplugged became fashionable on MTV, there were these people who never plugged in, like the guys I knew who stuck with bluegrass—some of them are extraordinarily successful. Because they never amplified, and they stuck with the idiom, and they became incredibly good at it. Guys like Ry Cooder.

Q: Country Joe & the Fish were probably the most political of the bands that made this transition to folk-rock and psychedelic music.

BM:It partially had to do with the mission of Country Joe & the Fish. We were interested in stopping the war. Our thing was political action. Somehow, it became manifest to us at some point in time that we'd have a bigger voice if we stepped into a popular idiom. And we did. So we had a perception; this perception proved correct. We were glad we were there, because it made us more relevant. For a minute there in time, we were bigger than Pete Seeger. Folk music receded for a period of time. Folk music will always remanifest itself, because it's our country. The story of America is in its folk music. Rock and roll is a musical period, so to speak, in American culture. But folk music is a durable part of American culture. Popular music of the time gets dated by the time. Folk music is sort of timeless, in a way, I think.

Q: What do you think set the Fish the most apart from other bands working the same musical territory?

BM: A couple of things. One is obviously the overtness of the lyrical content. But the other thing is, it really was a soup to nuts band. We played in a wide variety of styles. We had records where no two cuts were alike. Our records could be a real schizophrenic experience to listen to, 'cause we didn't have an overall sound sometimes. We went from sort of ragtime to blues to jugband to blah blah blah. You could call us a jack of all trades and a master of none, in some respects. But we really had sets where we played ten songs, none of which had any real musicological relationships to the one that preceded [it]. So I think we weren't looking for a sound, although we had a sound that was this sort of Farfisa organ semi-psychedelic sound that ultimately became a niche. And then the band died as a result, probably.

Q: You mean after the first three albums, which were your most popular?

BM: Yeah. But the early albums, the tunes vary from track to track a lot. And they show that we were capable of addressing a number of different idioms, I think.

It wasn't simply political commentary. Other bands alluded to drugs; we talked about them. You know, straight-up. The Grateful Dead didn't have any songs that actually directly talked about drugs. "Riding this train, hiding cocaine"—that's later on. I don't know how many albums in that was for them. We were talking about weed right on the first record, getting high. By the second record, we were singing the LSD commercial. So we were overt—not simply politically overt, sociologically overt. In other words, we said it. We also said "fuck," you know. We were the guys who said what other people alluded to. Everybody else had the message coded in there. There was no mistaking who was doing what. In the relative sense, it was right there in the lyric content.

Q: You had another link to the acoustic folk scene by using Sam Charters as your producer.

BM: Sam didn't know how to record rock and roll. Our recordings are drier than a lot of the rock recordings of the period. But they have a sort of almost classic finish. I mixed "Section 43" on the first Country Joe & the Fish EP. Sam put that fade-in, fade-out thing on in the first [LP], on [the re-recording of "Section 43" for] Electric Music for the Mind and Body. They're really not that different, in some respects. They really are the same thing. [They're] not tremendously different, structurally. They're certainly recognizable as the same thing, and the structure's identical. The solos change. But that's probably understandable in the year gap between them. Those records don't sound the way we sounded. Because we were playing louder, at a more distorted pace, than other people seemed to be able to capture on vinyl. They made us turn down for it.

But I learned a lot from Sam. We were compatible. He understood jugband music, and we were part jugband. Sam was a very knowledgeable musicologist. We were all musicologists, because we were all folk musicians, and all folk musicians are musicologists to a greater or lesser degree. know my early American music, and I know my idioms, the ones that I was interested in, really well. Modern guitar players don't know the history of recorded guitar and particularly the history of recorded blues guitar as well as I do. And didn't know those guys, like I did. I sought them out, and the guys who were still alive, I played with them. Reverend Gary Davis stayed at my house. Mance Lipscomb, I led him around. Bukka White, I drove him around in my car. Jesse Fuller, I knew him.

Sam knew [blues] folks, and had sought them out. We'd talk blues a lot, and with ED [Denson], we'd talk it. ED is a musicologist too, and understands the early blues idiom, from Charley Patton, that line, going from the '20s race records through the '60s, really well, that forty years of recorded American music. It's a finite body of work, and knowable in some respects.

Talking about someone who never made the transition [to electric music]...Stefan Grossman. He was the second guy that Ed formed a record company with; they formed Kicking Mule together. Stefan really stayed within the folk idiom very much. But he was another incredible musicologist.

Q: You were the biggest rock band on Vanguard Records, which had enormous success in the early-to-mid-1960s with folk music. They didn't seem to adapt to well to the rock market, though.

BM: Vanguard didn't make it [as far as adapting to the electric music]. It is what it is, the past is what it is, we lived our lives the way we lived our lives. No complaints.

[Vanguard] had only two artists really that were selling at all, [one of whom was] Joan Baez. It was a privately owned company by two guys, and their dad worked in the art department. He was more conservative than his sons. And they were conservative. They were very much moved by the left, and had very principled ideals, and they very much stood by our political stance. I don't think they understood the drug thing at all. But they backed us up politically. I know that would not have been possible on one of the major labels. And I'm not sure it would have been possible with Elektra, especially after Elektra merged [with a major label]. So maybe we were where we were supposed to be, based on the content of what we were doing.

Q: It didn't seem like Vanguard knew what to do with a lot of the rock bands they signed in the late 1960s.

BM: Not a clue. I knew David and Tina [Meltzer, of Vanguard band the Serpent Power] both, and Sam of course befriended them, he produced them. They were conservative. They never really understood, appreciated, or wanted to be, really, in the rock music business.

Q: I've been told by someone else I interviewed that Vanguard actually paid more attention to the classical part of their catalog than the pop side.

BM: Absolutely did. Because they considered it to be a safer bet and more revenue-producing, and a better investment over the long run. I'm telling you, it was this conservative, little family-run business. Conservative and sort of left-wing at the same time (laughs).

Q: So they were politically to the left, but aesthetically conservative?

BM: Yeah. In retrospect, they weren't bad people. And like I say, if you look at us on a content basis, I'm not sure anybody else would have...we would have had to get smaller to have such freedom. It was the biggest company we could go to who would afford us that level of freedom, probably.

There's no doubt of a connection between the Weavers, who were the Vanguard act, the act that put Vanguard on the map, and Country Joe & the Fish. To me, the quintessential Vanguard Records act is the Weavers. They were still selling big in the '60s. They were their big sellers. The Weavers defined Vanguard Records in many ways. Which, by the time we got there, was only a decade beforehand. [Even to record the Weavers in '55] was dangerous. And recording Country Joe & the Fish in '67 was dangerous, in some ways. We were very much in the tradition of the label. So in that sense, I'm proud to be on the same record label as the Weavers, and among the three big acts on Vanguard. 'Cause there are no more big acts that will ever be on Vanguard.

Q: ESP was probably one of the few other labels that would have given you freedom, and they were smaller.

BM: Or Folkways. I think we were at the biggest place we could be and still have unrestricted content. Although not everything was unrestricted. Our second album cover is totally retouched, 'cause it offended [Vanguard executives] Maynard [Solomon] and Seymour [Solomon's] father, who was in the art department. In reality, on the second cover, I'm wearing a full-dress Nazi uniform with a swastika on the sleeve. Gary Hirsch was wearing a pope outfit with a real pope hat. That offended them. It would be a depiction of a real Catholic priest, and a real Nazi officer. To us, though, the symbolism had a lot of shock value.

Q: "Fixin' to Die" is the most famous Fish song, and had been on your first EP, but wasn't issued on Vanguard until the second LP. Were they possibly nervous about putting that out, and not willing to put it on the first LP.

BM: Nope. It just didn't fit [on the first LP], as I remember. We had a bunch of songs. We put together sort of what seemed to fit in the group, and nobody was trying to restrict anything. If you listen to what's on the first record, there's some stuff there that's fairly shocking for its time. I mean, there's a righteous potsmoking song on the record. Owsley came by our sessions. I don't think it was that at all.

We were in this groove, so to speak. We put together an array of songs and considered them aesthetically, and that's what seemed to fit together. We had other tunes that were proposed and didn't seem to fit, that's all. I think we made a good song selection on there. It was our best-selling record. It was a better selling record in the long term, and has been over time, than the one with "Fixin' to Die." Interestingly enough, Electric Music for the Mind and Body is the perennial best seller of Country Joe & the Fish, the first record. I think it's the most authentic, and in a weird way, what was on there fit together.

The tune [of "I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die Rag"] is awfully close to "Muskrat Ramble" by Kid Ory. It's not really "Muskrat Ramble," but it's obviously heavily influenced by it. If the song has a musical progenitor, that would be it. But it doesn't have a lyrical progenitor, as far as I know.

Q: You saw the Byrds when they were just starting out?

BM: I saw 'em at Ciro's [in L.A. in 1965]. I had met McGuinn and Crosby in L.A. before the Byrds formed. As a matter of fact, when I first met McGuinn, he was singing like Beatles songs on the acoustic guitar. It was at somebody's house. He had a like a Beatles haircut and he sang Beatles songs, and I thought, man, is this lame! And I've since come to actually sort of love his music.

It was cool. It was one of the first times I heard a rock band playing music that I could relate to, playing like in the folk idiom. It was sort of folk music amplified. But it wasn't anything that I thought was so cool that I wanted to do it myself (laughs). On the other hand, it seemed sort of loud, and it seemed sort of crass and a little commercial and their clothes were too tight. It didn't have the intellectual cachet.

You [have to consider] how bad amplification was in those days. Now, one of the things that's reinvigorated the concept of acoustic music, is sound systems are so wonderful today that you can play it and really cover an audience. But there was only one way to speak loud, and that was to get an amplifier and plug into it. Nowadays, you don't have to do that. They make acoustic mikes now, they sell acoustic guitars that are amplified. They have a really true tone, they're amplified well, it sounds like an acoustic guitar, and it can be turned up incredibly loud. So you could actually do a bluegrass concert in a stadium now, 'cause amplification has reached that level of ability that it can propel acoustic music to a large crowd.

The only way that you could propel music to a large crowd, a really big crowd, in the sixties, was with amplified music. That's why amplified music arose, and why amplified folk-rock arose. Now, it's not really necessary. If you want to play acoustic instruments, that's okay, because the PA system will carry it now. So part of the reason for it is really entirely technological. It's technological innovation and sound amplification that's made it possible to return to the acoustic idiom.

I played in recent years with just a guitar. I've played acoustic guitar in the modern Fillmore Auditorium, and it fills up the whole place. But if I had stepped on that stage in 1967 and tried to play acoustic guitar, you wouldn't have hardly been able to hear it. The sound system just couldn't deal with it. So the only way you were going to impress anybody is to have a stack of amplifiers, and then you could make the place rock. We had to go to amplified music in order to deal with crowds that were 10,000 people and more. Because there was no way of doing that effectively with an acoustic instrument, to capture an audience that large.

In the summer of '68, we went from pop festival to pop festival to pop festival. Literally. These giant, unstructured outdoor events. The only way you'd ever have a chance in one of those is playing...I was driving 600 watts of guitar music in those days. But it wouldn't be necessary today, because today the modern PA system is capable of propelling an acoustic instrument loud and with clarity over to a very large crowd. You can fill a stadium with an acoustic guitar these days.

Q: You played at a lot of rock festivals, including of course Monterey and Woodstock. It seemed like those were in some way an outgrowth of the folk festivals of the early-to-mid-'60s, with a lot of the musicians at the rock festivals having gone to and played at earlier folk festivals. What were the similarities and differences?

BM: By the time you get to someplace like Monterey, it's kind of the end of the folk era and the beginning of the rock era. But an enormous number of those performers had been on the folk circuit. So there was an acceptance among the performers and the musicians. They understood in some ways that the difference between acoustic and electric music was a distinction that content was more important than the medium. It was the content of what you were doing that mattered.

But the pop festival was extraordinarily different from the folk festival in one major way. All the folk festivals that I went to—and this is true to this very day, with bluegrass festivals, which have maintained sort of that folk tradition—is that a significant part of the audience was people who played and sang themselves. They would line the exterior of whatever the festival was. Hundreds of people, playing guitars, playing together, singing kind of singer-circles or whatever it was. And rock music never had that participatory element in it.

One thing I remember in Monterey that was a hangover from the folk tradition is they had the main stage show, but they also had these little stages that were set outside of the main arena that were forums for sort of like smaller bands or unpaid bands to play. They kept that part of the folk tradition as part of the festival. They made sort of like a place off the main beat, where people could play, in keeping with the folk tradition. They had jugglers and comedians and small bands. I went and jammed with somebody in a little place, and it was a big deal, 'cause I was one of main stage guys, coming to the little place to jam. But that part of it dropped away. It ceased to exist. I think Monterey had that because it was part of the folk festival tradition, to provide a forum for the non-star players, to put a place outside the grounds where people could get together and less accomplished folks could play music. I think that's one of your transitional things.

Q: I think rock festivals drew a lot more people who would have been non-participants in musical events at folk festivals, and who in fact would never have come to a folk festival.

BM: There's no doubt that the reason why so many performers, particularly young performers, made that transition from folk and rock was accessibility. I mean, they wanted to reach a wider audience. When electric music gained some authenticity and acceptance even among the folk audience, they got to take those people with them. And then of course got to carry it to the much wider audience that was just going there to dance. I realized, as I was making the transition, what happened is it made it a lot easier to survive playing music. Because once we started playing rock and roll, all of the sudden we were in venues where people could care less what we were saying or what we were doing. As long as the backbeat was there, they were happy. And they were too drunk anyway to know what we were doing, exactly. But it allowed us to book ourselves in proms and dances and things, where the content of what we were doing didn't matter one bit. Because the whole point of it is, there were a bunch of guys up on stage with a backbeat, screaming guitars, and you could dance to it. That's all that mattered.

Without kidding, it would have made no difference in Berkeley had we been rock musicians or folk musicians. But when it came to getting those gigs in Concord and Lafayette and Antioch and the rest of the East Bay and down on the Peninsula, Berkeley or San Francisco, we could have stayed folk musicians. But all of the sudden, we began picking up work at like the armory in Concord or whatever, playing the rock and roll dance. And they didn't care if we were from Berkeley. They didn't even care what we were singing about. They probably couldn't hear it anyway, 'cause PAs were so bad in those days. And they didn't care that we were folk musicians, or how authentic it was. All they wanted was the backbeat, and music to get drunk and fight by. It was basically, it was a bunch of drunk kids showed up at the armory, danced, and then when they got really drunk, they started beating each other up, and that was the end of the dance. We played a lot of places like that in the early days of the band when we were unknown, where we were just a fungible rock and roll band on the edge of town. But we performed a function, which was sort of, "who cares what they're doing as long as it's really loud and the drums are crashing." We were just bad enough to fill the bill, too.

It's amazing how, in my lifetime, I'm seeing rock and roll really come in from the edge of town where it had no....it was less than music, you know what I mean? To having, like, legitimacy. While rock music had no legitimacy, folk music always had legitimacy. We sort of assumed that we were like doing this sort of base art form that really had no legitimacy, and people didn't write seriously about. I mean, writers didn't write seriously about it. It's like there are no base art forms left anymore. Everything gets artistic consideration these days. But that wasn't true in the world of the '60s. Folk music was art because it was the authentic music of the people, particularly songs about oppression, social issues, and things like that. But rock music was just like an idle pastime. That's what the teenagers did at the edge of town; they got drunk and they had fights and went to rock music.

Rock music was sort of like what commercial wrestling is to sports. It was fake sports, and rock music was sort of like fake music. It wasn't like real. A lot of rock music was kind of mindless when we sort of joined up. And I'll tell you, it wasn't the most appealing audience in the world. At least growing up in the Bay Area, we knew when we were leaving town and we were playing a quote "gig" unquote versus playing for a music audience in town. When we just got those bookings as a rock band and we went to play those outposts of non-culture like Napa and Concord and Antioch, places where the unthinking rock crowds lived, we knew that no one was listening at all, in a way. We had no expectation that any of them really cared anything about what we were doing. Maybe two kids who had been to the city before and had some idea of what was going on there would come up and tell us that they actually appreciated us.

But for the most part, the music had no legitimacy, and so we had no legitimacy. We were just sort of providing a service, which was playing rock music. We were on a rock circuit, not on a music circuit. The folk circuit was like a legitimate circuit where people sat down and they listened, and you made these like inside references, and everybody understood 'em, because it was like an idiom. You said, this is Child ballad #163 and everyone nodded in knowing approval, "Oh, it's a Child ballad."

Q: By the time of rock festivals like Woodstock, the whole issue of whether you played electric or acoustic being important had disappeared. People just accepted what the music was, as opposed to the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, when Dylan caused so much controversy by playing electric rock.

BM: Of course, the rumored appearance throughout the [Woodstock] festival was gonna be if and when Dylan was gonna show up. The rumor was because we were in the neighborhood, he was gonna show up and play. And I don't think it would have made a bit of difference if it had been acoustic or electric, or there would have been any expectation one way or the other.

Folk rock educated the mass audience to folk music and created an acceptance of folk music that probably hadn't existed previously. It built the sort of modern genre of musician that can slip back and forth between the two mediums, and it's perfectly okay. And people understand it.

There really was an element of betrayal in the folk days. [If] you used your skills honed in the folk arena for the profane art of rock music, there was like an ethic in the folk movement that didn't permit that. When you hear the stuff about Dylan having done that, it was that folk ethic that got offended. Obviously that ethical barrier has been largely erased over time. People accept moving back and forth, recognizing both as being different idioms. But it's almost like learning folk music was a privilege and carried with it a social responsibility not to be like corporate America or something. Somehow when you electrified, it was betraying this gift you'd been..."we allowed you to hang out with us and learn how real people played and now you're using it in the commercial arts." I can't describe it to you. But there was something mildly offensive about a real folk musician playing electric music. We're fortunate today, because those distinctions have been abolished, I guess.

Q: How do you view folk-rock's legacy in terms of the impact it continues to have on music and society today?

BM: The tradition in American folk music of political activism goes back at least to Joe Hill. But certainly to the '30s. The music business has maintained its connection with progressive politics, and progressive politics has therefore maintained its connection with youth. And I think that's an outgrowth of the '60s. But by the same token, I think the '60s are an outgrowth of the '30s. What I mean is, there's no doubt of a connection between Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie.

I think I have some degree of perspective, because I've been out of the music business so long. I have remained socially active, I work in social justice causes. I'm a public defender, and I work on statewide criminal justice issues for indigent people. So people who know me know that actually I'm doing the same thing I've always done, just a different manifestation of it, and maybe in some ways a more age-appropriate manifestation of it. It's tough to be on the road now, at my age. I'm not putting down the people my age who are on the road, but I know that the career I'm doing now, I have another ten-twelve years easily. Lawyers are not old at sixty-five. Musicians are ancient. Especially rock musicians, geez, although John Mayall's still on the road. It's not impossible. I still play, and I love it. I really enjoy playing now. I like getting out there, three, four, five times a month, maybe occasionally doing a tour for eight to ten days, but [I'm] glad I don't have to.

Things were very black-and-white back then. You were either on the right side or the wrong side. In many ways, I'm as idealistic as I was then. But I'm not so naive as to believe that things are black and white, or that people are on the right side or the wrong side. Because it's a lot more complicated than that. You get progressive thinking in conservative places. It's never an entirely simple equation. Life is not so simple.

I have some fundamental beliefs that have not changed. Certainly I thought the war in Vietnam was wrong, and I still think the war in Vietnam was wrong. I haven't been persuaded from my point of view. As a matter of fact, it's been interesting watching all the people who were responsible for that war, people like Robert McNamara, saying it was a mistake, and agreeing with me over time. I like being vindicated.

Special reprint granted by the author, Richie Unterberger. No part of this interview may be reprinted, copied or altered without the written permission of the author. @2003/2010 All rights reserved.

Click logo to connect with Richie on Facebook!

Click to listen to Section 43!